Article courtesy of The AFR View.

Labor gets it that gas is the global bridging fuel between coal and renewables. And markets are responding already.

Two weeks ago, The Australian Financial Review suggested that the first response to a critical gas domestic gas shortage should be to find more gas, rather than taking export gas away from Australia’s overseas customers and intensifying the global energy crisis.

When it’s allowed to work, the market can provide most things, from a fast COVID-19 vaccine to more essential fuels. This week suggested it could happen with energy too.

The Senex joint venture between South Korean steel maker Posco and Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Energy plans to spend $1 billion expanding its Surat Basin gas production in Queensland to take pressure off the big three Gladstone LNG exporters.

Santos plans to spend $1.2 billion on a pipeline from the Wallumbilla gas hub in Queensland down to Newcastle, running through its huge Narrabri gas project in north-western NSW. It will bring more Narrabri gas to the eastern consumer markets and break open another north-south pipeline route from Queensland as well.

The new investment will diversify the gas supply just as federal and state energy ministers agreed on Friday to give more powers to the Australian Energy Market Operator to identify both winter and summer gas supply problems in time for next year, and to contract more unused gas storage if it is needed.

Yet this week federal Resources Minister Madeleine King – who just last month was among those threatening to pull the trigger to restrict the gas exports fuelling Australia’s biggest trade surplus – effectively rebuked the NSW and Victorian state governments for discouraging or even effectively vetoing the extraction of the gas resources that lie beneath their feet.

“The Queensland gas industry is working hard to boost supply, when supply elsewhere is in decline”, Ms King said.

Queensland’s gas resources were financed by the commitments of long-term foreign buyers – not just big international energy companies — that have helped power the rise of Asia’s middle class. These include Korean buyers that are well-placed to join Australian producers in transitioning to low-carbon hydrogen as a primary source of energy.

World needs Australian resources in transition

Yet Ms King points out that, while NSW and Victoria restrict gas development, many people would be “astounded” at how much these states still rely on coal, for lack of cleaner gas.

And that is valid globally too, where Australia has a comparative advantage in supplying the LNG that can be a bridging fuel between the exit of dirty coal and full reliance on renewables. “Without the Australian resources sector, the world does not have net zero,” Ms King declares.

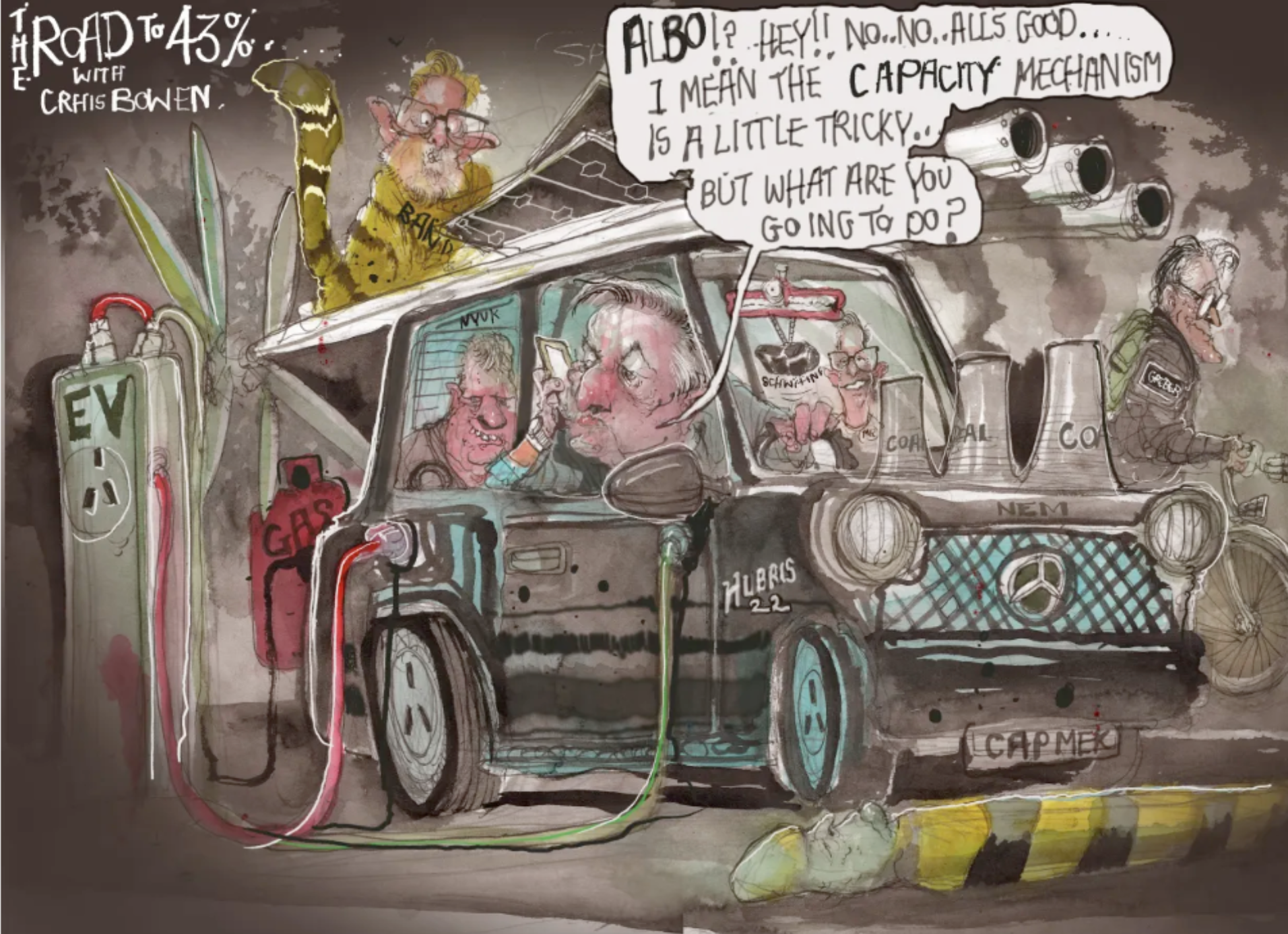

The net zero target and the interim Australian target of 43 per cent are hard enough without smashing public confidence in an orderly energy transition with a hasty end to gas investment, as demanded by activists.

Australia is on the way to achieving an emissions reduction of about 30 per cent through what it is doing now, mostly rooftop solar. Labor has also made a good start on offshore wind farms, where Australia lags behind the rest of the world.

But most of the remaining 13 per cent will come from electric cars, a massive $20 billion rewiring of the grid to connect more renewables and, above all, from industry.

Big manufacturers will have to wait until year-end to see how the cap and trade system of the safeguard mechanism will work. Many of them are already struggling with gas shortages. Killing off new gas investment might be the last straw for many.

The immediate global energy crisis is largely down to Vladimir Putin, who is banking on gas-dependent European economies to break before the stubborn Ukrainians on the battlefield. Yet if Europeans co-operate, they can substitute or conserve enough gas for their energy markets to adapt. If they hold out until February, they will have seen off Mr Putin, who has only this one card to play.

But the geopolitical energy shock of 2022 is really only a dress rehearsal for the challenges of the overall energy transition to 2050.

In Australia, it will be the biggest change to the economy since it was liberalised and opened up to foreign competition in the 1980s, and there will be similar upheavals elsewhere in the world.

Managing the present crisis should provide some confidence that Australia can handle the bigger disruptive transformation to come.