Article by Greg Jericho courtesy of the Guardian

It is great for our economy, but it also means Australia’s economic base has become very narrow.

In February, for the first time ever, Australia had exported $8bn more goods than we had imported for the third consecutive month. This seemingly good news however hides the current lack of strength in our exports sector and that we are reliant on iron ore now more than ever.

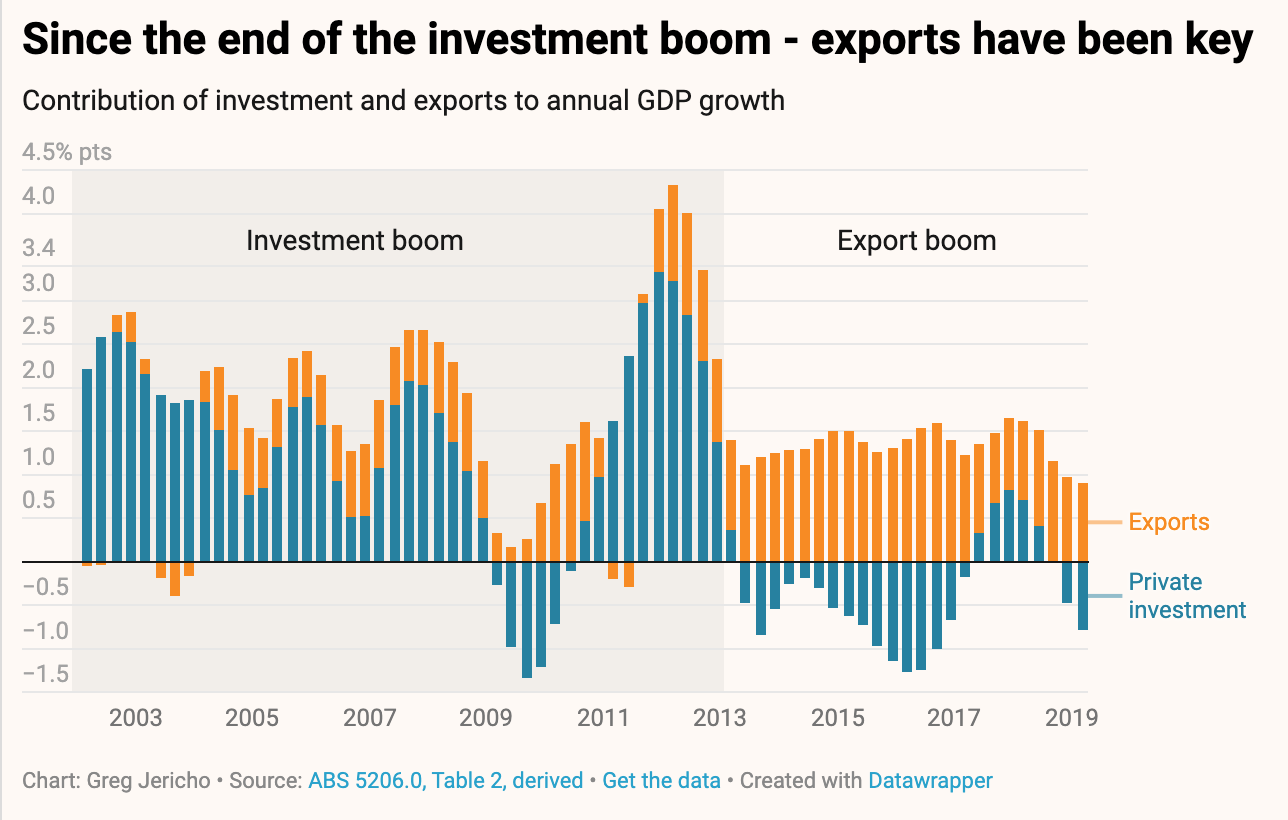

It almost goes without saying that our economy very much needs exports to keep growing.

Essentially in the private sector there are three things that make up and drive our economy – household spending, private investment, and exports.

During the mining boom, private investment was king. All that construction of mines, and roads and rail associated with the mines, drove our economy and sent masses of revenue into the government’s coffers.

But once the mines were built, the boom shifted to exports, and up to the pandemic, the switch from investment to exports had been total:

Exports are much more erratic than investment, and exporting iron ore doesn’t require anywhere near the number of workers as does building a mine, so the shift did create some problems. But at least the export boom was happening.

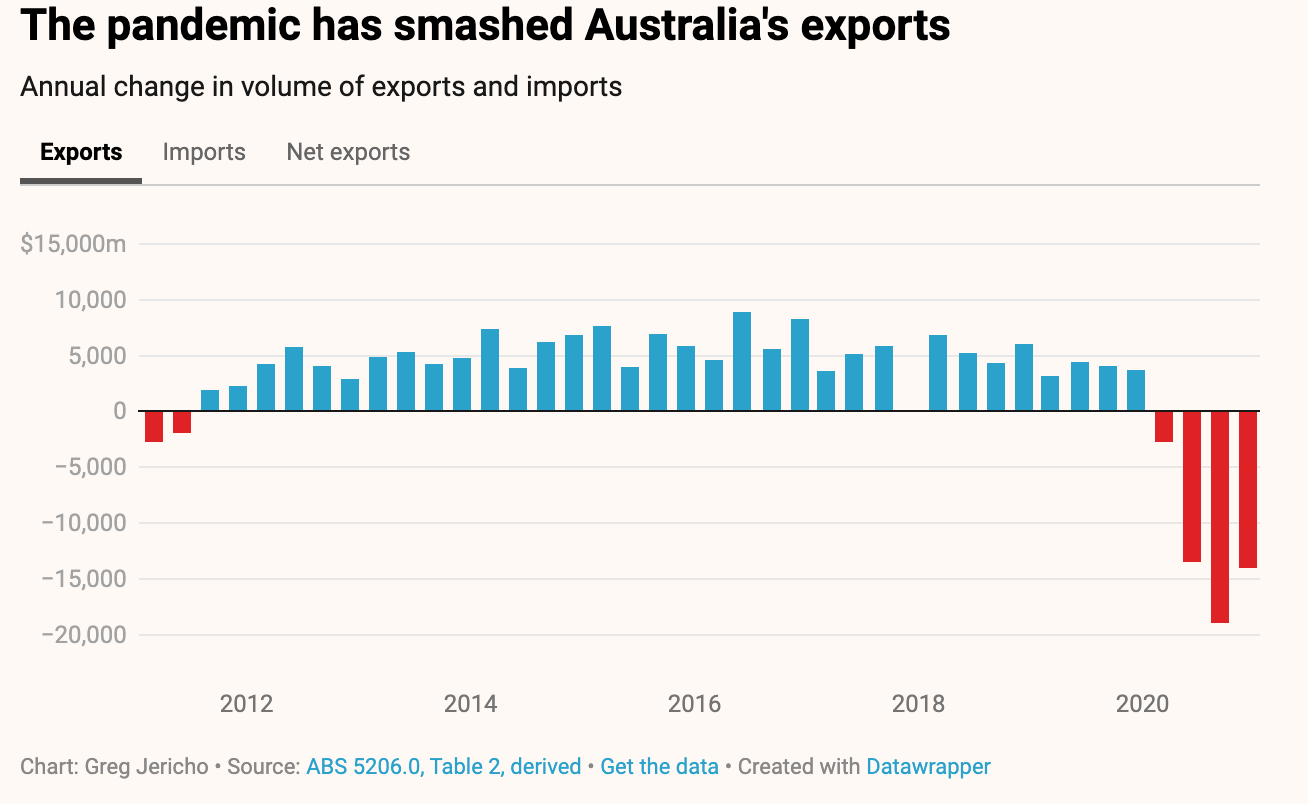

And then the pandemic came along and ruined things:

In the last quarter of 2020, Australia exported nearly $14bn less than it had a year earlier – a 12% fall.

But the overall hit to our economy was not as great because we also reduced how much we imported.

Imports actually reduce our GDP (because they involve sending money out of the economy) so when we import less it actually increases our GDP growth.

But in the wonderfully convoluted world of economics that does not mean we want to reduce imports, because when we import more that is generally a sign that our economy is actually healthy – it means we are buying consumer items and also buying things needed to build and produce goods and services here.

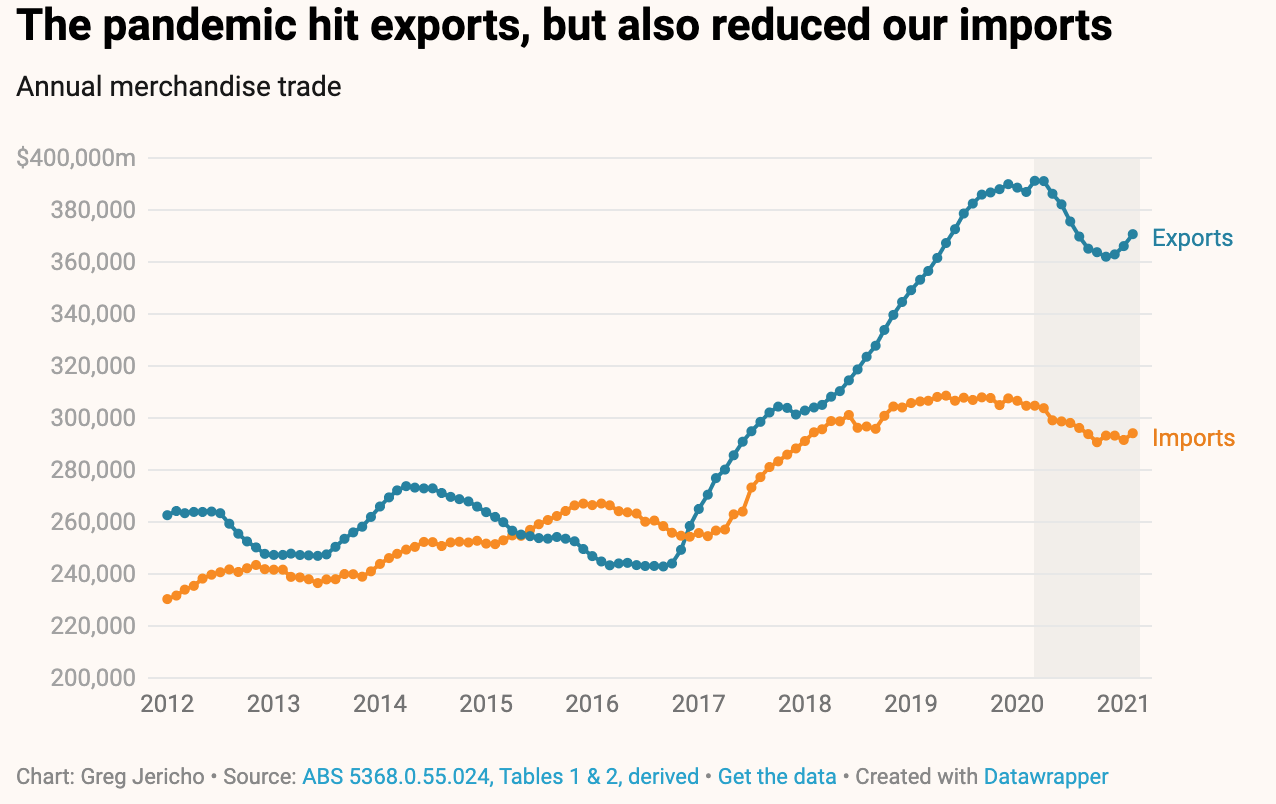

And so when we crow about our record run of an $8bn monthly merchandise trade surplus, we need to realise that is as much about reduced imports as it is about exports.

In reality our exports of goods have fallen, but so too have our imports:

And there really is one thing that is keeping our trade surplus going – iron ore. Over the past year, iron ore made up 41% of our total goods exports.

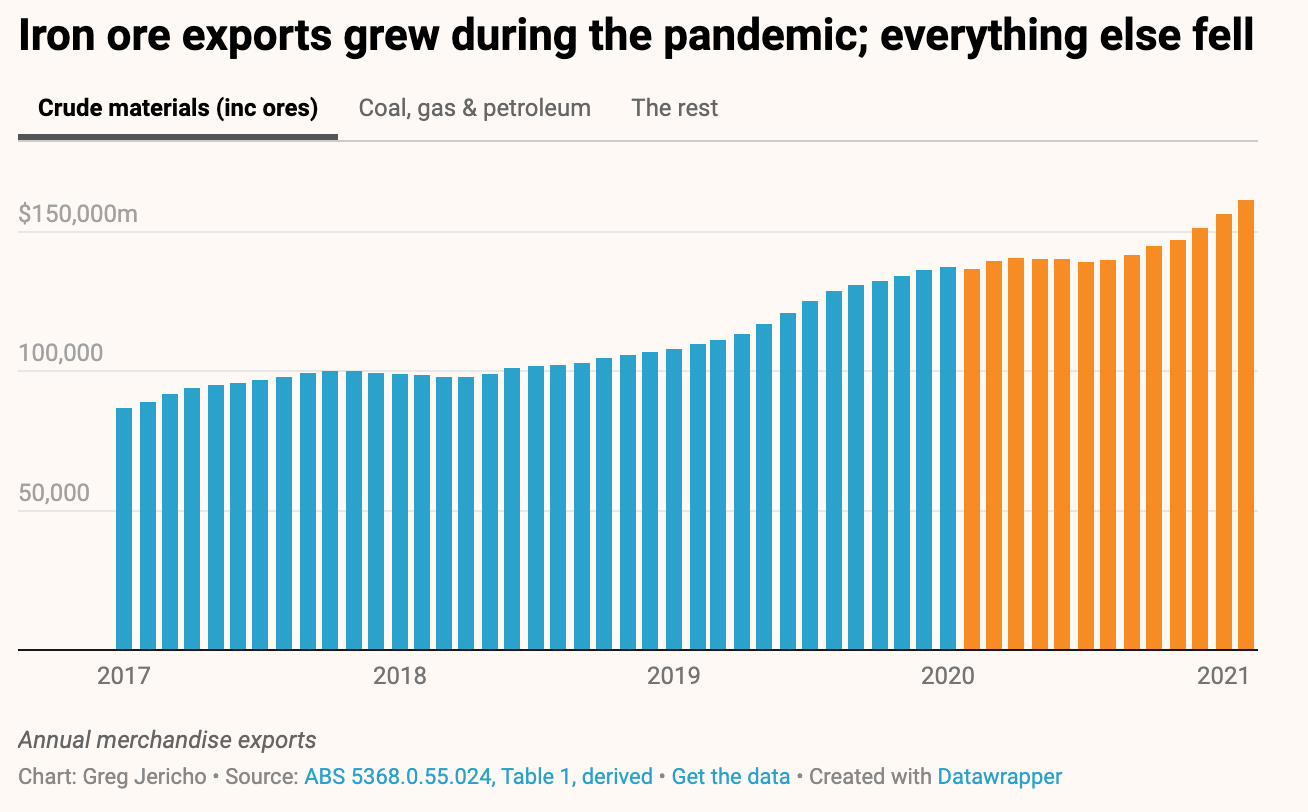

While everything – including coal and gas exports – fell, the demand for iron ore kept on keeping on:

It is great for our economy that we have such a large supply of iron ore, but it also means Australia’s economic base has become very narrow – we are incredibly reliant upon iron ore exports to power growth.

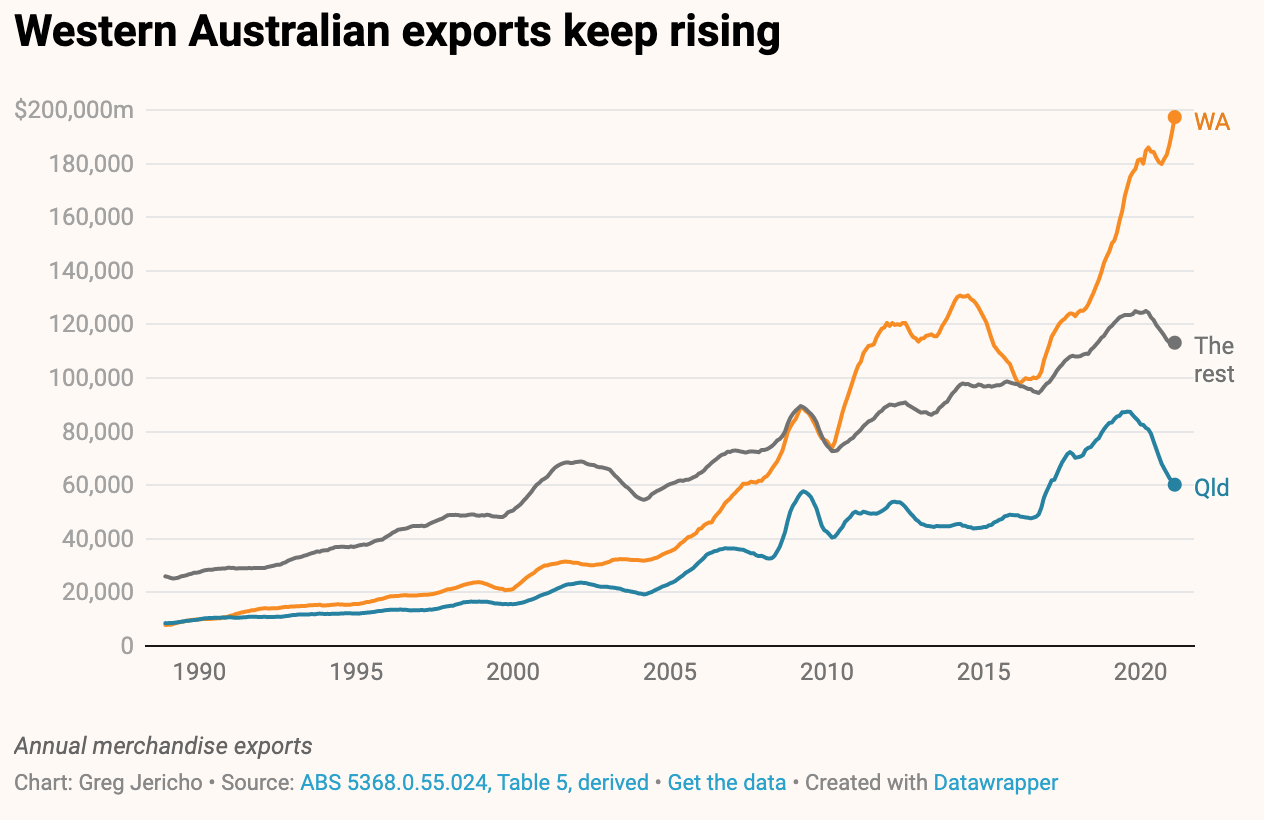

It also means that Western Australia has become even more the dominant source of Australia’s exports. While exports through 2020 from other states fell (including the coal and gas dominant Queensland), those from WA kept on rising:

More than half of Australia’s goods exports now come from Western Australia – at the start of the century it was just under a quarter.

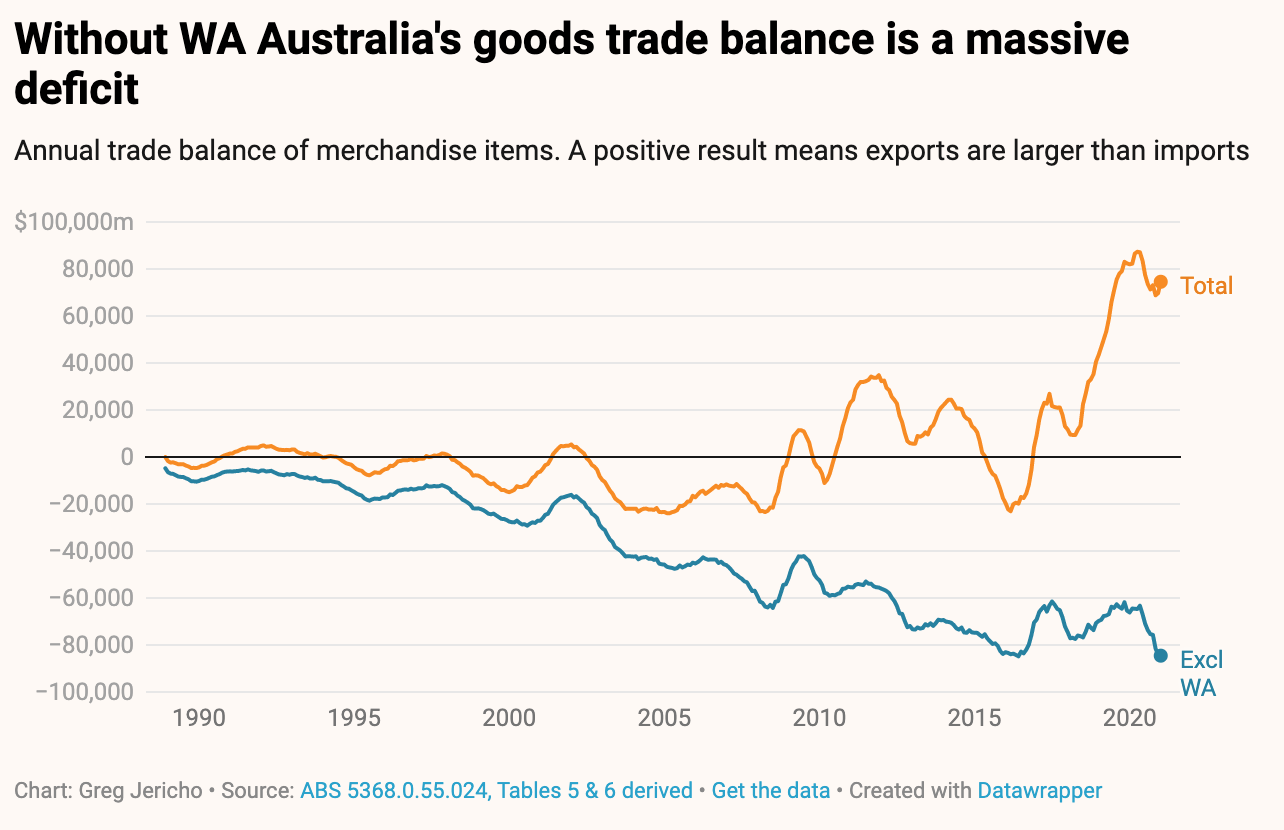

And it means that when we talk about Australia’s trade surplus, we really are talking about Western Australia. Yes, we have had three months in a row with a trade surplus above $8n, but if we excluded WA from the total, our trade deficits would have been among the worst ever recorded.

Indeed, all states and territories excluding WA recorded one of the biggest ever goods trade deficits in the past 12 months:

But while it is clear the export side of our economy is incredibly dependent upon iron ore, there is some good news on the imports side of things.

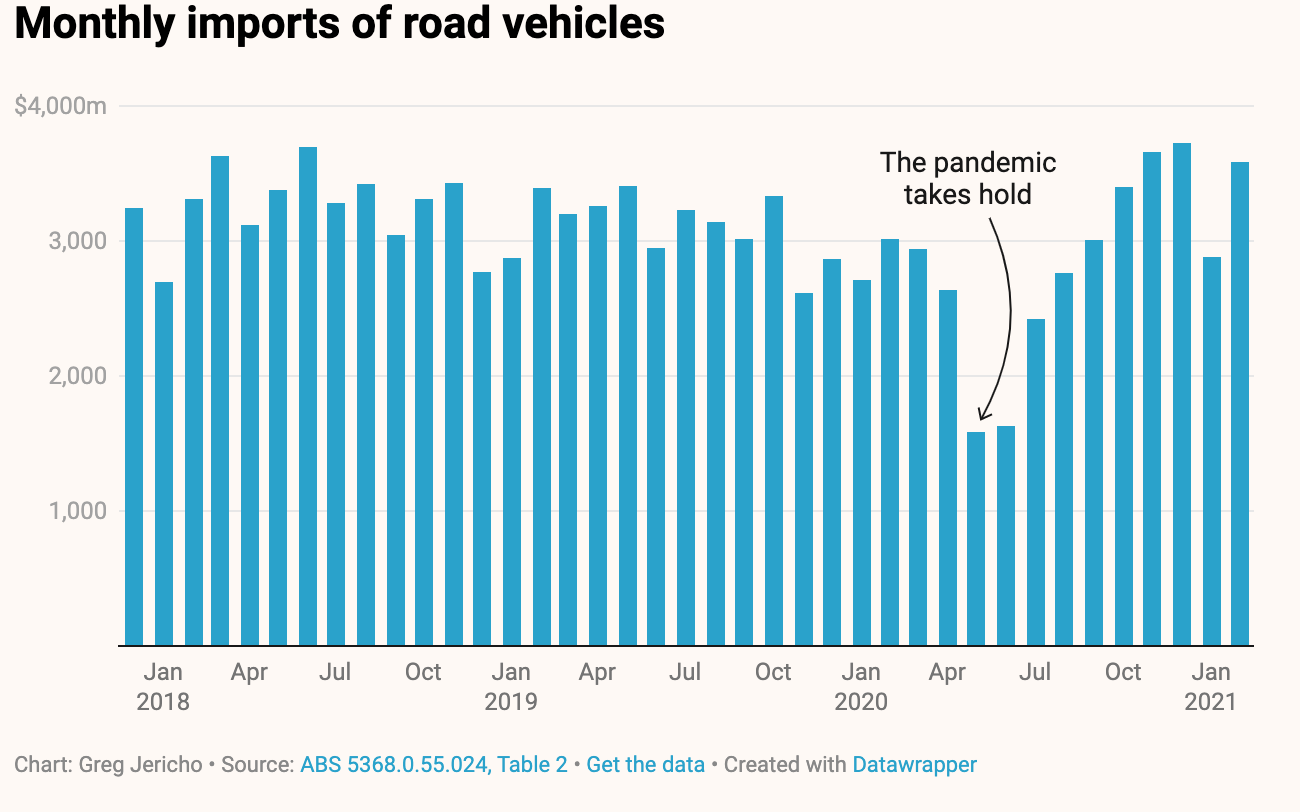

Given we lack any real domestic car industry, overwhelmingly all new car sales will come via imports. The pandemic put a very fast halt to people buying cars – due to a combination of inability to shop due to lockdowns, and fear over the future. But in February we spent a near-record amount importing road vehicles:

That might be bad for our trade surplus, but it does suggest our confidence to make a major purchase is fully returned, and is a good sign for the economy.