Article by Paul Kent courtesy of the Courier Mail.

While the Socceroos’ intentions are good with condemning Qatar’s poor human rights record, their words ultimately mean nothing if they still attend the World Cup, writes Paul Kent.

As seems to be the modern way, Australia’s Socceroos believe strongly enough about Qatar’s human rights record to publicly condemn their World Cup hosts this week.

Not enough to boycott the tournament, though.

Good manners is just one of the casualties of this modern trend of virtue signalling. It comes from a high moral ground, at least that’s the belief, so the Socceroos feel no shame that, having been invited to dinner, they are now complaining about the food.

Some have described their three-minute video, released Thursday and which saw them attack Qatar’s human rights record and its ban on same-sex relationships, as courageous.

But for there to be an act of courage, doesn’t there have to be risk?

The Socceroos have risked nothing but a rolled eye with their comments. FIFA certainly won’t bar them, or even castigate them, the Qatar government won’t arrest them, the tournament will go on.

Other nations have planned their own protests. Denmark will wear black, nine nations will wear “One Love” armbands.

For them all, it is a protest in the social media age. Do as I say, not as I do.

Where once an athlete’s protest was their action, now it is mere words.

When times were simpler Australians never much felt of an inclination to politically motivate their sport. Their politics was considered a private matter, never a lack of conscience or care.

Politically speaking, though, Australian athletes have nearly always been happy to keep the two apart.

When the United States boycotted the Moscow Olympics in 1980 in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, 64 countries invited to the Games supported the Americans and also boycotted, although Australia sent a team.

The Australian government supported the boycott but left the decision up to the individual sports, so the Australians competed under the Olympic flag, and not the Australian flag, to show their participation was not officially sanctioned.

But the athletes were there; faster, higher and stronger.

By then sport and politics had well mixed.

When Cassius Clay was at the Rome Olympics a Russian reporter wandered along, almost certainly with mischief in his mind, asking how it felt to win a gold medal for a country where he could not sit in a restaurant and order something to eat.

“Russian,” he said, “we got qualified people working on that.”

Not enough, it turned out, and certainly not quick enough.

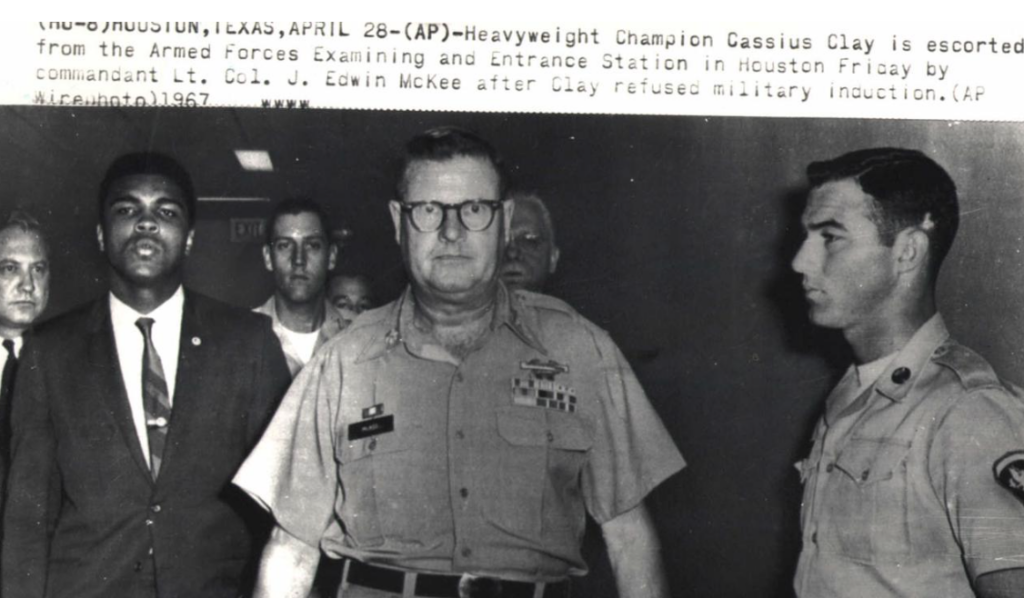

Clay soon changed his tune, renamed himself Muhammad Ali and became the most influential athlete of the 20th Century as he fought the war on civil rights and Vietnam.

To do so, all he had to do was surrender the heavyweight championship of the world, then considered the greatest prize in sports, to make real his statement. He refused to fight in Vietnam even though his fighting would have been little more dangerous than exhibition fights to entertain the troops on R&R.

There was a nobility in his sacrifice.

The power of sporting celebrity has grown considerably since, mostly on the back of Ali and those who followed him with his civil rights protests.

When Tommie Smith and John Carlos held their gloved black fists to the air at Mexico in 1968 Australian Peter Norman was standing to their right with a silver medal and an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on his chest.

Will the modern protester be remembered with the same reverence?

In Ali’s case, and the Black Power Salute, their legacy was equal to the weight of their risk, so both endure.

But until recently the sacrifice belonged to the individual.

The Socceroos’ protest comes with the protection of their sport. If a price is to be paid, Australian soccer will face it, not the players.

Australian cricket captain Pat Cummins has vowed to no longer endorse sponsor Alinta Energy, presumably in between stints in India and its 285 coal power plants.

We saw it happen a week earlier when the Australian netball team declared it would join teammate Donnell Wallam and boycott the Australian uniform that had its new sponsor, the mining company Hancock Prospecting.

Wallam was protesting comments made not by Hancock Prospecting owner Gina Rinehart but those of her father, Lang Hancock, made almost 40 years ago, and her teammates joined her protest.

Some apologists saw the protest as an opportunity for Rinehart to apologise for the comments of her father.

As abhorrent as his comments were, when we have to begin apologising for the behaviours of our forebears is the time we are all in trouble.

Wallam had every right to protest and withdraw, of course. But the team’s action took it beyond a personal protest with their decision to refuse the sponsorship made in “solidarity”.

Rinehart called it for what it was; virtue signalling, and a few days later withdrew her sponsorship.

Now, their protest has put their sport at risk, emboldened by timid administrators afraid to call it out and risk a social backlash.

Netball was $7 million in debt and in deep financial trouble. So much, the Super Netball grand final was sold to Perth at late notice earlier this year in a desperate cash grab.

The players didn’t like that either. They called the late switch to Perth “distressing” and “shattering” and called for a “change of culture”, even though Netball Australia chief executive Kelly Ryan explained it by saying netball was “in a really difficult financial position”.

It makes you wonder where the players think the money is coming from.

Broadcast money and sponsorships are the two great cash cows in this country.

Netball fails to justify its price as a television product for years, bouncing around the networks because it struggles to attract ratings, and just dropped the ball with the other.

And this won’t make more people want to watch it.

Rinehart loomed as a saviour, particularly after the lesson of the grand final sell-off, but the players’ politics saw an end to that financial windfall. It has not cost the team, but their entire sport.

Like the Socceroos, their intentions are true but their aim is off.

Now, their protest has put their sport at risk, emboldened by timid administrators afraid to call it out and risk a social backlash.

Netball was $7 million in debt and in deep financial trouble. So much, the Super Netball grand final was sold to Perth at late notice earlier this year in a desperate cash grab.

The players didn’t like that either. They called the late switch to Perth “distressing” and “shattering” and called for a “change of culture”, even though Netball Australia chief executive Kelly Ryan explained it by saying netball was “in a really difficult financial position”.

It makes you wonder where the players think the money is coming from.

Broadcast money and sponsorships are the two great cash cows in this country.

Netball fails to justify its price as a television product for years, bouncing around the networks because it struggles to attract ratings, and just dropped the ball with the other.

And this won’t make more people want to watch it.

Rinehart loomed as a saviour, particularly after the lesson of the grand final sell-off, but the players’ politics saw an end to that financial windfall. It has not cost the team, but their entire sport.

Like the Socceroos, their intentions are true but their aim is off.